#1: Introduction

Within a month or so of arriving here, I decided that everything I thought I knew about Indian history, culture, and politics was wrong.

Dear friends,

Greetings from New Delhi, India.

As some of you know, but many may not, I currently live and work here in the Indian capital. My job involves going to a corporate office every day and doing writing, research, and other tasks for the director of a fairly reputed Indian company. Professionally, it’s a creditable life: I get to travel around the country and encounter an industry and a work environment I would never have otherwise. It also entails a good deal of drudgery (like all jobs), and the hours are demanding. The biggest perk is getting to meet and talk to interesting people from across Indian business, civil society, academia, and politics. Doing so has hugely enriched my life here, professionally, intellectually, and personally.

The story of how I got here involves a university grant, a solo train journey around northern India, and some searching personal decisions. But the key facts are two, one proximate and one remote. The proximate reason for my being here is that, during my first visit to Delhi over the summer, I met someone who, to my amazement, offered me a job after a single conversation. If this has never happened to you, I can confirm it’s a thrill to the ego. But I hadn’t been looking for any job, so I didn’t initially accept. Some time passed, including the aforementioned train journey and a return to the US, before I realized it was definitely what I wanted to do.

The other reason has to do with why I would want to be in India in the first place. Many incredulous and bewildered Indians have put this question to me since I arrived, which itself says something about Indian perceptions of their own country relative to the West. Interestingly, few if any of my friends at home expressed a similar incredulity when I told them I was going: as if it were self-evident that any of us might one fine day pack up and move across the world. Now, maybe my friends’ non-surprise is just a reflection of the kinds of people I hang out with (or, conversely, of their view of me). But I think their reaction is also indicative of a common Western attitude towards India as the natural venue in which to enact the archetypal secret fantasy of bourgeois life: dropping out, leaving “normal” life behind, confronting one’s alienation, and embarking on a journey of self-discovery. Individual reception of this fantasy ranges from wistful desire to priggish skepticism; but the basic cultural presumption is, I think, that those who pursue it are worthy of respect, if a little eccentric. For this reason, shipping off to India can be a socially condoned act with minimal apparent justification. (It goes without saying that, in this fantasy, India stands less for anything concrete about itself than for a general sense of exoticism and newness, which is the whole point.)

This potent mix of ignorance and longing—along with its concomitant of surprising life choices that somehow fail to surprise—has propelled many generations of Westerners faddishly descending upon India in, as it has often seemed, a “fit of absence of mind.” Certainly it was central to both the theory and practice of the British Raj, that rich stomping ground for second sons and assorted Oxbridge miscreants. Likewise, if more affably, with the Hippie Trail and its poor rerunning in the eat-pray-love phenomenon. And a trace of the old listless romance is unmistakable even in today’s expat scene, notwithstanding its overabundance of journeyman consultants and young professionals climbing the back stairs to a Washington career.

I can’t profess any special preexisting Indophilia beyond a general sense of needing to drive off the spleen, and to that extent, I suppose I fit the mold of the innumerable waves of shallow drifters who preceded me. But, for what it’s worth, I do have one distinctive connection to this country, without which I would not be here (or, if I would anyway, my coming would at least be underdetermined, à la second sons, hippies, and consultants).

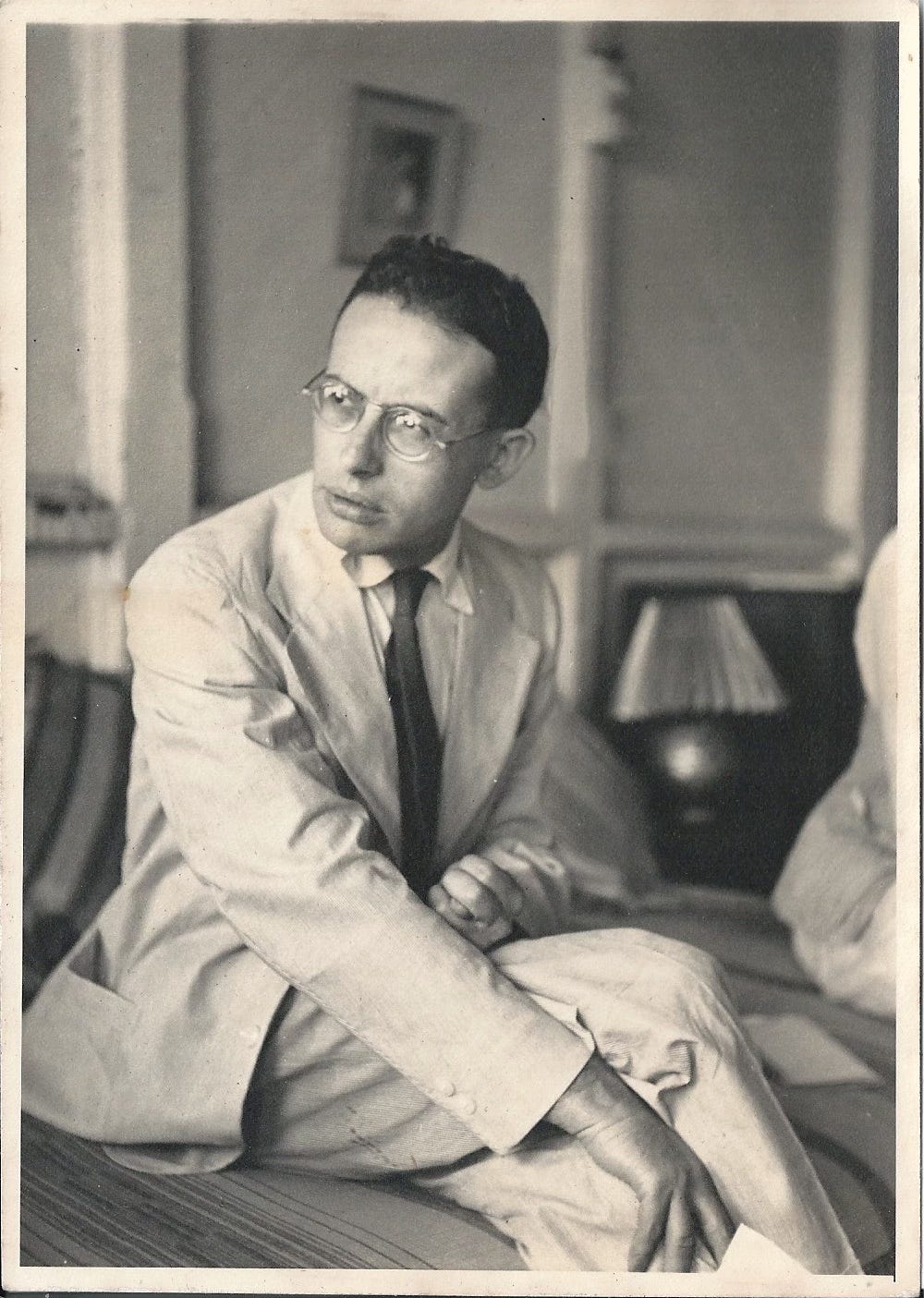

My paternal grandparents, Hazel Whitman and Sidney Hertzberg, were American activists for Indian independence. Their interest in India was an extension of their shared socialist and anti-war activism in the US, which was also how they met. They spent long periods in India around the time of independence and immediately after. My grandfather in particular kept up his interest, going on to work as an Asia specialist at the UN and an American correspondent for several Indian newspapers. Family lore holds that he was intimate with Nehru and acquainted with Gandhi. He later played a role in securing and conducting Nehru’s first American TV interviews, and wrote a documentary on Gandhian nonviolence that may have helped plant the idea in the minds of certain American civil rights leaders.

So, at least, go the stories. And to me they are stories, since stories are all I know of my grandparents. They both died long before I was born, and anyone they interacted with in India is liable to be dead, too. Some details of their lives here might be historically verifiable, but most are lost. Compounding matters, my grandparents’ subcontinent fixation then skipped a generation, and my own father and aunt added no new memories to those of the printed khadi textiles and Ganesha miniatures that filled their childhood home. I am the first member of my family to live in this country for seventy years. I wish I could retrace Sidney and Hazel’s steps here; more to the point, I wish I had a clear enough idea of my grandparents that retracing their steps would be meaningful to me. I’m not here to uncover their legacy in India, because I wouldn’t know what to do with it if I did. This is a strange, more than a sad, thought for me. But I take comfort all the same in the knowledge that their presence here is somehow the distant cause of mine.

—

The premise of writing a newsletter while living far from nearly every important person in your life is to lessen the distance. In practical terms, this ought to mean giving you, the reader, “updates” on what I’ve been up to, just as I might if we were meeting for lunch. I fear this is neither an easy nor an especially interesting premise for me to deliver on. Writing about myself in the sense of recording day-to-day events has never been a very compelling or fruitful exercise for me, at least not when intended for public consumption. These are not notes for a future memoir; I am just thinking out loud.

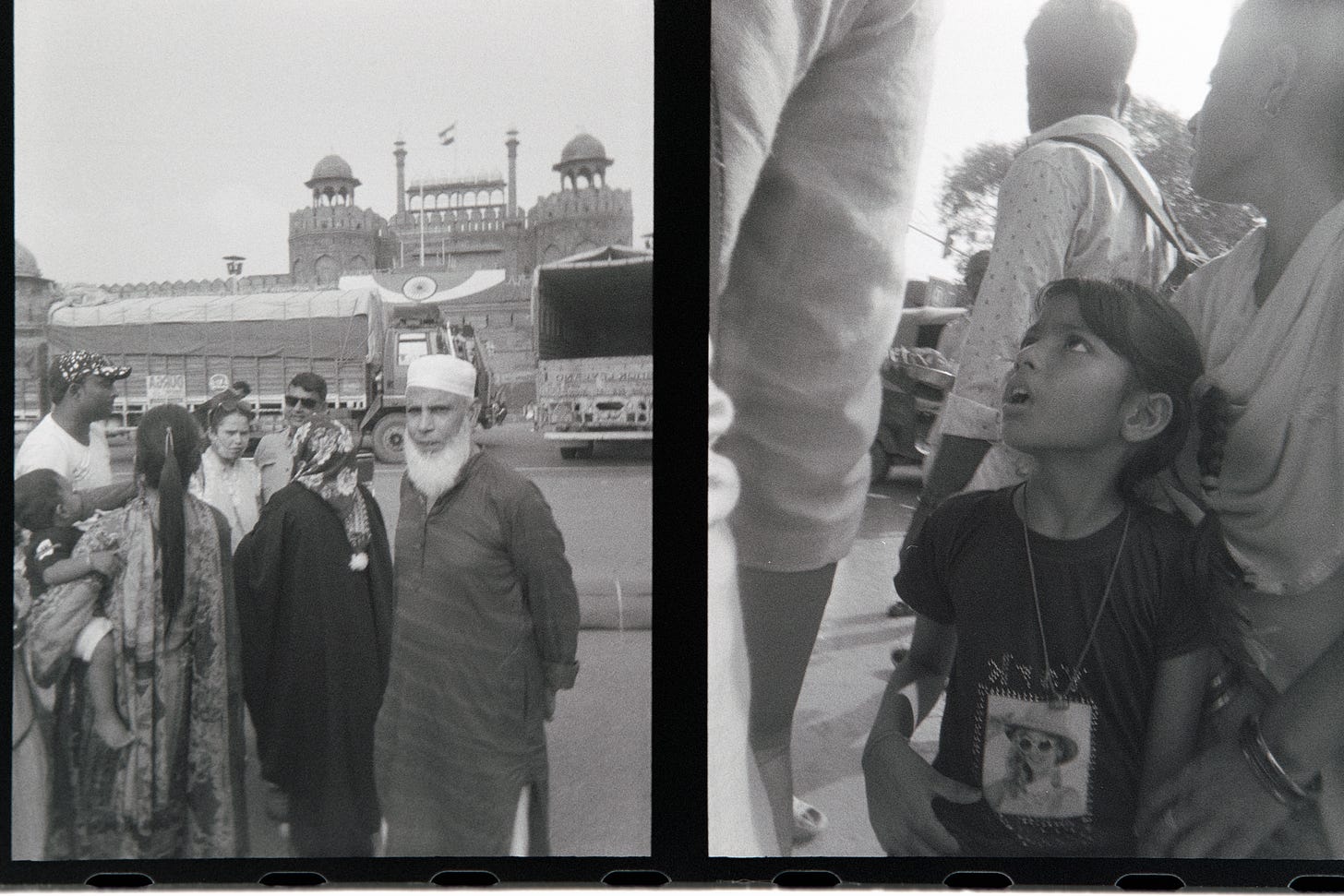

More vexingly, there are many aspects of daily life in India, of being a foreigner here, and of my personal life as a non-resident American that I find it difficult to give expression to either verbally or in writing. India, and especially Delhi, is startlingly familiar in some ways and utterly alien in others. If you have been to Delhi before, you know that there is a definitive sensory experience of the city that is more easily felt than described. All the same, I can try: visually, it consists in the panoply of colors; the “sun” that appears as an orange smudge against opaque gray (in all seasons, you can look right at it); the ubiquitous hand-painted signs cheerfully announcing addresses, public inquiries, businesses (extant and not), and religious slogans; and the amazingly discordant geometries of vehicle traffic, people, and public space, which give the impression one is viewing everything through dutch angles. Aurally, it is the many-layered panorama of human, animal, and mechanical noises, some with discernible origins but most dissolving into an incessant background thrum punctuated, and forever dominated, by car horns. (Pure silence is unknown.) Above all, it is sensuous: the inundation of skin, nose, and eyes with an air impossibly thickened by heat, dust, moisture, smog, and uncountable aromas. In Delhi, you discover that air really is a substance: that it can be swum though like water, worn like a clinging garment, or choked on like grit.

I have had the feeling of apprehending this sensory picture in its fullness only twice: once in the first seconds I spent in Delhi, coming out of a Metro station into a typical street scene; and a second time, much later, sitting alone in the minaret of the Jama Masjid suspended above Old Delhi. I wouldn’t expect you to know what it’s like any more than I knew before coming here, or than someone who had lived only in Delhi could know what it’s like to sit in the center of an Icelandic moss field.

—

Over and against this kind of public-oriented diary-keeping, I am much more comfortable writing about my intellectual development as an observer of India. The best part of living here has been, joyously, the very thing that most motivated me to come: the prospect of being able to widen my perspective and get some understanding of this country. Although “understanding” is not exactly what I would call it so far, except in the sense that I now understand the infinitude of my own ignorance. Within a month or so of arriving here, I decided that, in addition to being lost amidst the expected strangeness of Indian culture, basically everything I thought I knew about Indian history and politics was wrong, and that as for that black box known as “Eastern philosophy,” I simply knew nothing at all.

This leads me to a related thought—and please don’t be offended, reader—which is the possibility that none of us know anything about anything at all. I used to think I was an educated layman with regard to India, with the rationale that I occasionally read what the highbrow Euro-American press had to say about it. For that matter, I still think I’m an educated layman on many topics (cultures, periods of history, systems of thought, styles of art) despite not having lived in most of the places where these things originated. Yet if a few weeks in a new place is enough to retire years’ worth of accumulated platitudes from the best available sources, what hope has the venerable institution of Educated Laymanship? Must we discard newspapers, books, and received wisdom in favor of first-hand experience? But where would that leave us? We can’t all become expats every time we want to learn about someplace new.

In the Indian case, this epistemological difficulty is made worse by the skewed representation of Indian voices in Western media. Elite liberals, who include nearly everyone you or I know, talk to, or read, tend to want to listen to other people like them, even when trying to get to grips with a totally unfamiliar society. Liberals around the world share each other’s enthusiasm for dialogue, and can generally carry it out in a shared language (English). There is nothing wrong or surprising about this. Cosmopolitanism may or may not be philosophically fundamental to liberalism, but it is certainly one of its most attractive symptoms in practice.

The problem with cosmopolitanism is that it sometimes breeds a patrician myopia equal to the provincial one it displaces. Rahul Gandhi, the half-Italian scion of the Gandhi-Nehru family and India’s main opposition leader, made headlines last year when he told a London audience that democracy had “disappeared” from India. (Nothing of the sort has happened.) Gandhi’s view is not shared by most Indians, but it is typical of the kind of views that get a sympathetic airing in London and New York. This is down partly to ideological predisposition, partly to sociological affinity. But the Gandhi-Nehrus, who enjoy a dynastic pedigree unequaled by any other political family in the democratic world, no longer run India, and likely never will again. The Hindu nationalists who have taken their place are much less interested in courting international opinion, which in turn takes less of an interest in them. This is to the great discredit of all parties.

The inability of people like me to understand places like India is basically a structural information problem. Liberal elites go on talking to each other to try to understand each other’s societies, even as they are increasingly baffled by their own. They fail to get alternate perspectives because of mutual distrust between liberals and non-liberals. Suffice it to say, there will be no viral appearances at the Oxford Union by any Narendra Modi surrogates anytime soon. Most Modi surrogates are openly contemptuous of humanistic education, and in any case lack the dazzling English skills of their Nehruvian counterparts. Most Oxford students think Modi is a fascist.

The problem I’m talking about may be particularly acute in India, but versions of it exist for every country. This passage, from an essay by Viri Ríos on AMLO’s huge popularity in Mexico despite his poor international reputation, captures the diagnosis well:

International commentators frequently rely on the perspectives of Mexicans who can speak English, hold degrees from U.S. universities, or work in corporate-funded think tanks to construct their own perception of Mexican reality. This method breeds a significant bias in a highly unequal society like Mexico, where the potential to study other languages and create a broad international network is limited to those at the top of the wealth distribution.

This is especially problematic given that upper-income earners are the primary source of support for opposing parties and form the base of opposition to [AMLO’s party]. Opposition supporters are well aware of their outsized influence outside of Mexico and have expended much effort in arranging private contacts with international media, inviting them to political events, and explaining Mexican politics from their own point of view.

—

This newsletter will be a record of my attempts to understand India. It will likely entail a lot of ranting, contradictory positions, abstruse references, impolitic provocations, and mystifying attempts at humor. I don’t understand India very well. You have my blessing to skim.

It won’t always just be about India. I may share thoughts on other topics that interest me (and you too, of course—who among my friends doesn’t salivate at the prospect of my analysis of Roberto Mangabeira Unger’s classic of jurisprudence, Knowledge and Politics?). I might also throw in the occasional personal reflection or cultural endorsement.

I will try to mention in broad strokes what important developments, if any, have occurred in my life since the previous edition. Earlier this month, for example, I was at the fabulous Jaipur Literature Festival, which I hope to share my thoughts on later. Since then, I’ve been in Lucknow, Rishikesh, and at an Ayurvedic retreat in Kerala (ditto). I’ve made a number of new friends while living here, who have been by far the greatest boon to my daily happiness and mental wellbeing (not to mention the project of learning about India—and, if you must, of myself). They may crop up in these letters from time to time.

One thing I can promise is lots of photographs, which even when forgettable are far more eloquent than anything I could ever write. (If you’ve just made it through the preceding 2,500 words—joke’s on you!)

I can’t say how many of these newsletters I will produce, or how regularly. I have much to say, limited space in which to say it, and little time given the haphazard cadence of my life here. I promise they won’t all be so lengthy. I am doing this first and foremost for myself, and that will probably come across in what and how I choose to write. But I am motivated by the thought that some of you might be reading, and perhaps getting something out of this. Indulge me.

Bravo, Wolf! Loved reading this and look forward to all future editions. Thanks for undertaking this project. I suspect that you might think or hope that the discipline, if that’s the right word, of writing down ideas and impressions of your experiences for others to read will lead to more insights and self-knowledge than if you wrote only for your own eyes. You’re probably right! The bonus is that we, your soon to be loyal readers, reap enormous benefits, too. Believe me, it’s much more interesting and thought-provoking to read an articulate account of someone honestly, uncertainly exploring new terrain - physically, psychologically and intellectually - than it is to read a polished professional account by someone duty bound to come up with a dead-certain thesis or conclusion designed to sell copies or satisfy readers’ prejudices and expectations. In other words, you go, Wolf! We’re with you.

What an engaging letter you’ve sent us, Wolf. I’ve never been to Delhi but have to Cairo and Beijing. And your sensuous description of the city brought those memories back better than I had kept them. Also, what you say about cosmopolitanism as a ‘symptom’ of liberalism, well, let’s just say you’ve well-joined the family business. Mabrook.